The Dagger basics page explained how Dagger can help you automate dependency injection in your app. With Dagger, you don't have to write tedious and error-prone boilerplate code.

Best practices summary

- Use constructor injection with

@Injectto add types to the Dagger graph whenever it's possible. When it's not:- Use

@Bindsto tell Dagger which implementation an interface should have. - Use

@Providesto tell Dagger how to provide classes that your project doesn't own.

- Use

- You should only declare modules once in a component.

- Name the scope annotations depending on the lifetime where the

annotation is used. Examples include

@ApplicationScope,@LoggedUserScope, and@ActivityScope.

Adding dependencies

To use Dagger in your project, add these dependencies to your application in

your build.gradle file. You can find the latest version of Dagger

in this GitHub project.

Kotlin

plugins { id 'kotlin-kapt' } dependencies { implementation 'com.google.dagger:dagger:2.x' kapt 'com.google.dagger:dagger-compiler:2.x' }

Java

dependencies { implementation 'com.google.dagger:dagger:2.x' annotationProcessor 'com.google.dagger:dagger-compiler:2.x' }

Dagger in Android

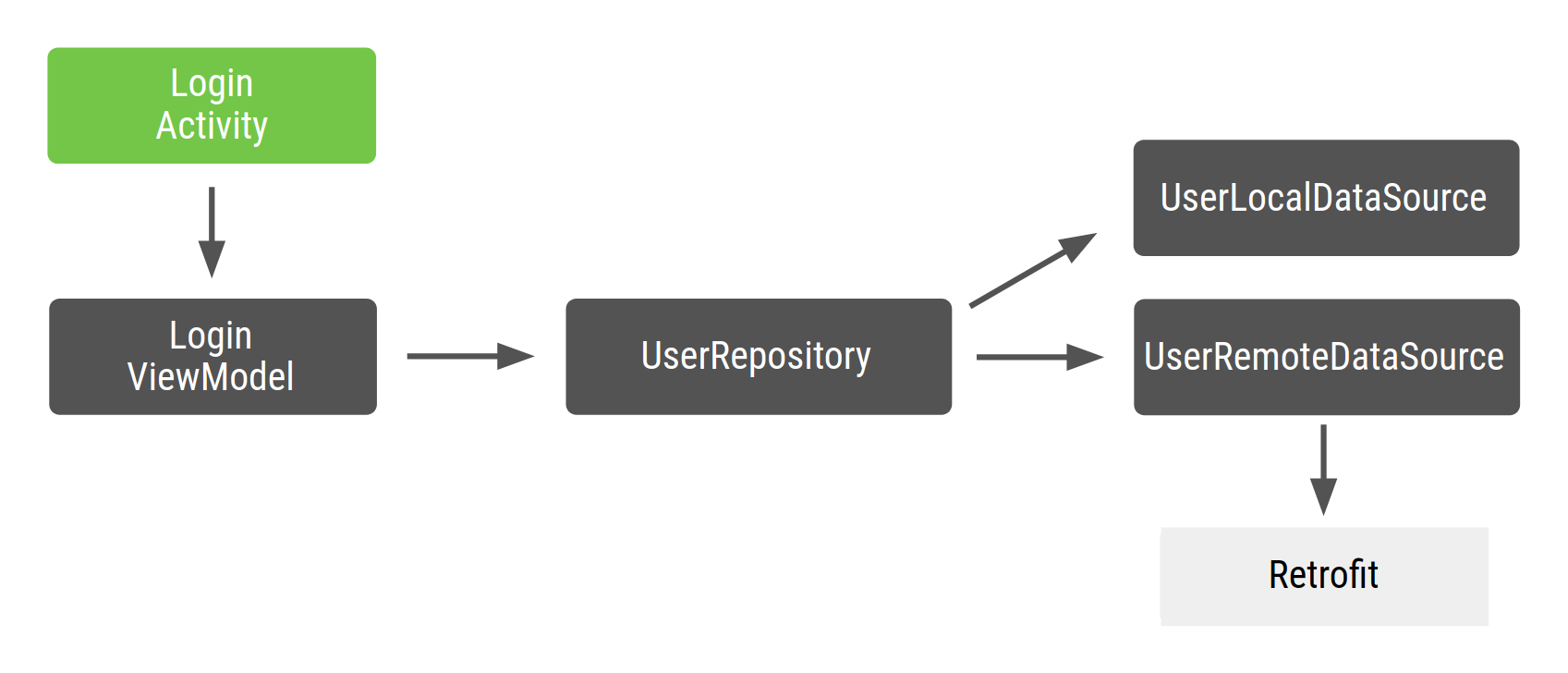

Consider an example Android app with the dependency graph from Figure 1.

Figure 1. Dependency graph of the example code

In Android, you usually create a Dagger graph that lives in your application

class because you want an instance of the graph to be in memory as long as the

app is running. In this way, the graph is attached to the app lifecycle. In some

cases, you might also want to have the application context available in the

graph. For that, you would also need the graph to be in the

Application class. One advantage of this

approach is that the graph is available to other Android framework classes.

Additionally, it simplifies testing by allowing you to use a custom

Application class in tests.

Because the interface that generates the graph is annotated with @Component,

you can call it ApplicationComponent or ApplicationGraph. You usually keep

an instance of that component in your custom Application class and call it

every time you need the application graph, as shown in the following code

snippet:

Kotlin

// Definition of the Application graph @Component interface ApplicationComponent { ... } // appComponent lives in the Application class to share its lifecycle class MyApplication: Application() { // Reference to the application graph that is used across the whole app val appComponent = DaggerApplicationComponent.create() }

Java

// Definition of the Application graph @Component public interface ApplicationComponent { } // appComponent lives in the Application class to share its lifecycle public class MyApplication extends Application { // Reference to the application graph that is used across the whole app ApplicationComponent appComponent = DaggerApplicationComponent.create(); }

Because certain Android framework classes such as activities and fragments are

instantiated by the system, Dagger can't create them for you. For activities

specifically, any initialization code needs to go into the onCreate() method.

That means you cannot use the @Inject annotation in the constructor of the

class (constructor injection) as you did in the previous examples. Instead,

you have to use field injection.

Instead of creating the dependencies an activity requires in the onCreate()

method, you want Dagger to populate those dependencies for you. For field

injection, you instead apply the @Inject annotation to the fields that you

want to get from the Dagger graph.

Kotlin

class LoginActivity: Activity() { // You want Dagger to provide an instance of LoginViewModel from the graph @Inject lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel }

Java

public class LoginActivity extends Activity { // You want Dagger to provide an instance of LoginViewModel from the graph @Inject LoginViewModel loginViewModel; }

For simplicity, LoginViewModel is not an Android Architecture Components

ViewModel; it's just a regular class that acts as a ViewModel.

For more information about how to inject these classes, check out the code

in the official Android Blueprints Dagger implementation, in

the dev-dagger branch.

One of the considerations with Dagger is that injected fields cannot be private. They need to have at least package-private visibility like in the preceding code.

Injecting activities

Dagger needs to know that LoginActivity has to access the graph in order to

provide the ViewModel it requires. In the Dagger basics page, you used

the @Component interface to get objects from the graph

by exposing functions with the return type of what you want to get from the

graph. In this case, you need to tell Dagger about an object (LoginActivity

in this case) that requires a dependency to be injected. For that, you expose

a function that takes as a parameter the object that requests injection.

Kotlin

@Component interface ApplicationComponent { // This tells Dagger that LoginActivity requests injection so the graph needs to // satisfy all the dependencies of the fields that LoginActivity is requesting. fun inject(activity: LoginActivity) }

Java

@Component public interface ApplicationComponent { // This tells Dagger that LoginActivity requests injection so the graph needs to // satisfy all the dependencies of the fields that LoginActivity is injecting. void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); }

This function tells Dagger that LoginActivity wants to access the graph and

requests injection. Dagger needs to satisfy all the dependencies that

LoginActivity requires (LoginViewModel with its own dependencies).

If you have multiple classes that request injection, you have to specifically

declare them all in the component with their exact type. For example, if you had

LoginActivity and RegistrationActivity requesting injection, you'd have two

inject() methods instead of a generic one covering both cases. A generic

inject() method doesn't tell Dagger what needs to be provided. The functions

in the interface can have any name, but calling them inject() when they

receive the object to inject as a parameter is a convention in Dagger.

To inject an object in the activity, you'd use the appComponent defined in

your Application class and call the inject() method, passing in an instance

of the activity that requests injection.

When using activities, inject Dagger in the

activity's onCreate() method before calling super.onCreate() to avoid issues

with fragment restoration. During the restore phase in super.onCreate(),

an activity attaches fragments that might want to access activity bindings.

When using fragments, inject Dagger in the fragment's onAttach()

method. In this case, it can be done before or after calling super.onAttach().

Kotlin

class LoginActivity: Activity() { // You want Dagger to provide an instance of LoginViewModel from the graph @Inject lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { // Make Dagger instantiate @Inject fields in LoginActivity (applicationContext as MyApplication).appComponent.inject(this) // Now loginViewModel is available super.onCreate(savedInstanceState) } } // @Inject tells Dagger how to create instances of LoginViewModel class LoginViewModel @Inject constructor( private val userRepository: UserRepository ) { ... }

Java

public class LoginActivity extends Activity { // You want Dagger to provide an instance of LoginViewModel from the graph @Inject LoginViewModel loginViewModel; @Override protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { // Make Dagger instantiate @Inject fields in LoginActivity ((MyApplication) getApplicationContext()).appComponent.inject(this); // Now loginViewModel is available super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); } } public class LoginViewModel { private final UserRepository userRepository; // @Inject tells Dagger how to create instances of LoginViewModel @Inject public LoginViewModel(UserRepository userRepository) { this.userRepository = userRepository; } }

Let's tell Dagger how to provide the rest of the dependencies to build the graph:

Kotlin

class UserRepository @Inject constructor( private val localDataSource: UserLocalDataSource, private val remoteDataSource: UserRemoteDataSource ) { ... } class UserLocalDataSource @Inject constructor() { ... } class UserRemoteDataSource @Inject constructor( private val loginService: LoginRetrofitService ) { ... }

Java

public class UserRepository { private final UserLocalDataSource userLocalDataSource; private final UserRemoteDataSource userRemoteDataSource; @Inject public UserRepository(UserLocalDataSource userLocalDataSource, UserRemoteDataSource userRemoteDataSource) { this.userLocalDataSource = userLocalDataSource; this.userRemoteDataSource = userRemoteDataSource; } } public class UserLocalDataSource { @Inject public UserLocalDataSource() {} } public class UserRemoteDataSource { private final LoginRetrofitService loginRetrofitService; @Inject public UserRemoteDataSource(LoginRetrofitService loginRetrofitService) { this.loginRetrofitService = loginRetrofitService; } }

Dagger modules

For this example, you're using the Retrofit networking library.

UserRemoteDataSource has a dependency on LoginRetrofitService. However,

the way to create an instance of LoginRetrofitService is different from what

you've been doing until now. It's not a class instantiation; it's the result of

calling Retrofit.Builder() and passing in different parameters to configure

the login service.

Apart from the @Inject annotation, there's another way to tell Dagger how to

provide an instance of a class: the information inside Dagger modules. A Dagger

module is a class that is annotated with @Module. There, you can define

dependencies with the @Provides annotation.

Kotlin

// @Module informs Dagger that this class is a Dagger Module @Module class NetworkModule { // @Provides tell Dagger how to create instances of the type that this function // returns (i.e. LoginRetrofitService). // Function parameters are the dependencies of this type. @Provides fun provideLoginRetrofitService(): LoginRetrofitService { // Whenever Dagger needs to provide an instance of type LoginRetrofitService, // this code (the one inside the @Provides method) is run. return Retrofit.Builder() .baseUrl("https://example.com") .build() .create(LoginService::class.java) } }

Java

// @Module informs Dagger that this class is a Dagger Module @Module public class NetworkModule { // @Provides tell Dagger how to create instances of the type that this function // returns (i.e. LoginRetrofitService). // Function parameters are the dependencies of this type. @Provides public LoginRetrofitService provideLoginRetrofitService() { // Whenever Dagger needs to provide an instance of type LoginRetrofitService, // this code (the one inside the @Provides method) is run. return new Retrofit.Builder() .baseUrl("https://example.com") .build() .create(LoginService.class); } }

Modules are a way to semantically encapsulate information on how to provide

objects. As you can see, you called the class NetworkModule to group the logic

of providing objects related to networking. If the application expands, you can

also add how to provide an OkHttpClient here, or how to

configure Gson or Moshi.

The dependencies of a @Provides method are the parameters of that method. For

the previous method, LoginRetrofitService can be provided with no dependencies

because the method has no parameters. If you had declared an OkHttpClient as a

parameter, Dagger would need to provide an OkHttpClient instance from the

graph to satisfy the dependencies of LoginRetrofitService. For example:

Kotlin

@Module class NetworkModule { // Hypothetical dependency on LoginRetrofitService @Provides fun provideLoginRetrofitService( okHttpClient: OkHttpClient ): LoginRetrofitService { ... } }

Java

@Module public class NetworkModule { @Provides public LoginRetrofitService provideLoginRetrofitService(OkHttpClient okHttpClient) { ... } }

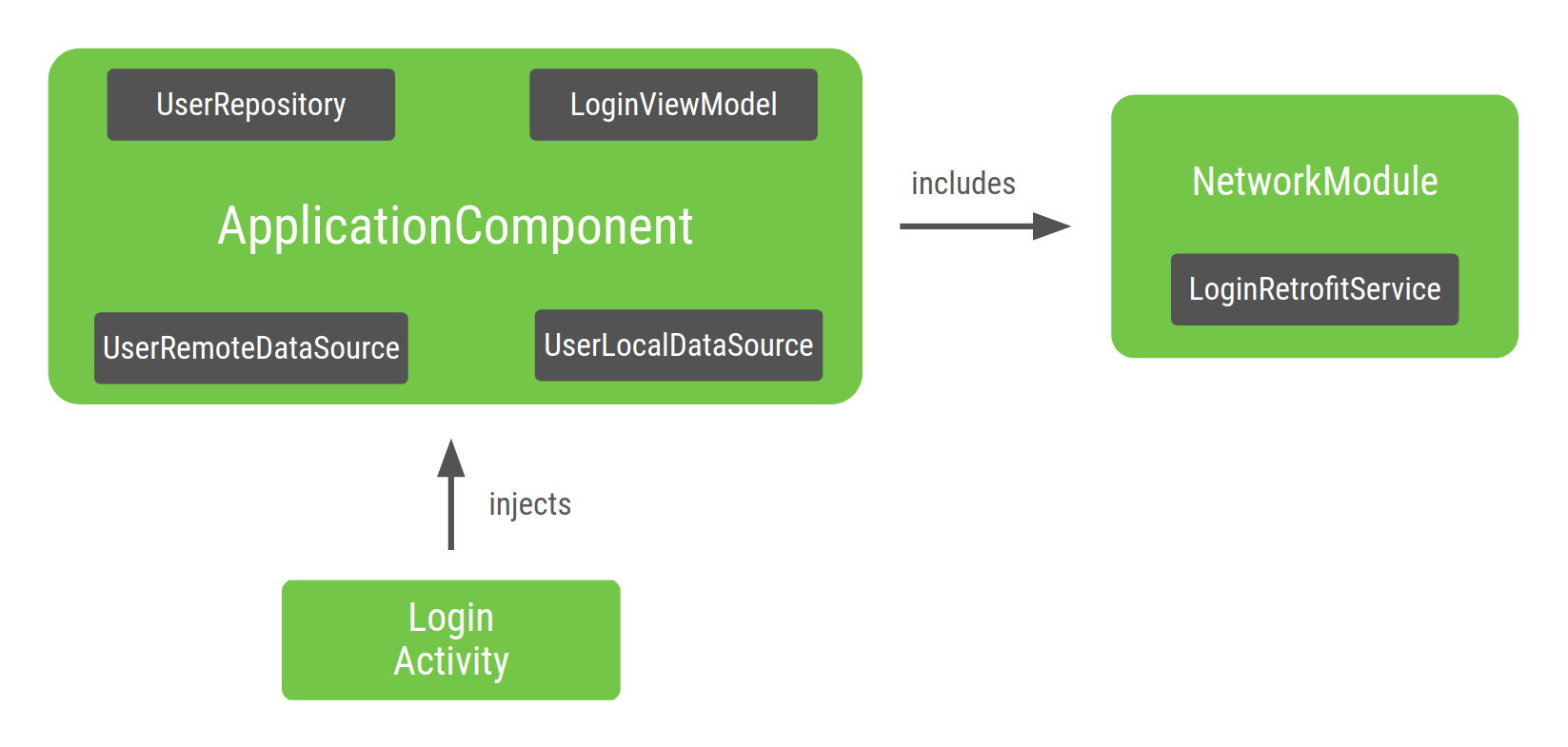

In order for the Dagger graph to know about this module, you have to add it to

the @Component interface as follows:

Kotlin

// The "modules" attribute in the @Component annotation tells Dagger what Modules // to include when building the graph @Component(modules = [NetworkModule::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { ... }

Java

// The "modules" attribute in the @Component annotation tells Dagger what Modules // to include when building the graph @Component(modules = NetworkModule.class) public interface ApplicationComponent { ... }

The recommended way to add types to the Dagger graph is by using constructor

injection (i.e. with the @Inject annotation on the constructor of the class).

Sometimes, this is not possible and you have to use Dagger modules. One example

is when you want Dagger to use the result of a computation to determine how to

create an instance of an object. Whenever it has to provide an instance of that

type, Dagger runs the code inside the @Provides method.

This is how the Dagger graph in the example looks right now:

Figure 2. Representation of the graph with

LoginActivity being injected by Dagger

The entry point to the graph is LoginActivity. Because LoginActivity injects

LoginViewModel, Dagger builds a graph that knows how to provide an instance

of LoginViewModel, and recursively, of its dependencies. Dagger knows how to

do this because of the @Inject annotation on the classes' constructor.

Inside the ApplicationComponent generated by Dagger, there's a factory-type

method to get instances of all the classes it knows how to provide. In this

example, Dagger delegates to the NetworkModule included in

ApplicationComponent to get an instance of LoginRetrofitService.

Dagger scopes

Scopes were mentioned on the Dagger basics page as a way to have a unique instance of a type in a component. This is what is meant by scoping a type to the component's lifecycle.

Because you might want to use UserRepository in other features of the app and

might not want to create a new object every time you need it, you can designate

it as a unique instance for the whole app. It is the same for

LoginRetrofitService: it can be expensive to create, and you also want a

unique instance of that object to be reused. Creating an instance of

UserRemoteDataSource is not that expensive, so scoping it to the

component's lifecycle is not necessary.

@Singleton is the only scope annotation that comes with

the javax.inject package. You can use it to annotate ApplicationComponent

and the objects you want to reuse across the whole application.

Kotlin

@Singleton @Component(modules = [NetworkModule::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { fun inject(activity: LoginActivity) } @Singleton class UserRepository @Inject constructor( private val localDataSource: UserLocalDataSource, private val remoteDataSource: UserRemoteDataSource ) { ... } @Module class NetworkModule { // Way to scope types inside a Dagger Module @Singleton @Provides fun provideLoginRetrofitService(): LoginRetrofitService { ... } }

Java

@Singleton @Component(modules = NetworkModule.class) public interface ApplicationComponent { void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); } @Singleton public class UserRepository { private final UserLocalDataSource userLocalDataSource; private final UserRemoteDataSource userRemoteDataSource; @Inject public UserRepository(UserLocalDataSource userLocalDataSource, UserRemoteDataSource userRemoteDataSource) { this.userLocalDataSource = userLocalDataSource; this.userRemoteDataSource = userRemoteDataSource; } } @Module public class NetworkModule { @Singleton @Provides public LoginRetrofitService provideLoginRetrofitService() { ... } }

Take care not to introduce memory leaks when applying scopes to objects. As

long as the scoped component is in memory, the created object is in memory

too. Because ApplicationComponent is created when the app is launched (in the

Application class), it is destroyed when the app gets destroyed. Thus, the

unique instance of UserRepository always remains in memory until the

application is destroyed.

Dagger subcomponents

If your login flow (managed by a single LoginActivity) consists of multiple

fragments, you should reuse the same instance of LoginViewModel in all

fragments. @Singleton cannot annotate LoginViewModel to reuse the instance

for the following reasons:

The instance of

LoginViewModelwould persist in memory after the flow has finished.You want a different instance of

LoginViewModelfor each login flow. For example, if the user logs out, you want a different instance ofLoginViewModel, rather than the same instance as when the user logged in for the first time.

To scope LoginViewModel to the lifecycle of LoginActivity you need to create

a new component (a new subgraph) for the login flow and a new scope.

Let's create a graph specific to the login flow.

Kotlin

@Component interface LoginComponent {}

Java

@Component public interface LoginComponent { }

Now, LoginActivity should get injections from LoginComponent because it

has a login-specific configuration. This removes the responsibility to inject

LoginActivity from the ApplicationComponent class.

Kotlin

@Component interface LoginComponent { fun inject(activity: LoginActivity) }

Java

@Component public interface LoginComponent { void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); }

LoginComponent must be able to access the objects from ApplicationComponent

because LoginViewModel depends on UserRepository. The way to tell Dagger that

you want a new component to use part of another component is with

Dagger subcomponents. The new component must be a subcomponent of the

component containing shared resources.

Subcomponents are components that inherit and extend the object graph of a parent component. Thus, all objects provided in the parent component are provided in the subcomponent too. In this way, an object from a subcomponent can depend on an object provided by the parent component.

To create instances of subcomponents, you need an instance of the parent component. Therefore, the objects provided by the parent component to the subcomponent are still scoped to the parent component.

In the example, you must define LoginComponent as a subcomponent of

ApplicationComponent. To do this, annotate LoginComponent with

@Subcomponent:

Kotlin

// @Subcomponent annotation informs Dagger this interface is a Dagger Subcomponent @Subcomponent interface LoginComponent { // This tells Dagger that LoginActivity requests injection from LoginComponent // so that this subcomponent graph needs to satisfy all the dependencies of the // fields that LoginActivity is injecting fun inject(loginActivity: LoginActivity) }

Java

// @Subcomponent annotation informs Dagger this interface is a Dagger Subcomponent @Subcomponent public interface LoginComponent { // This tells Dagger that LoginActivity requests injection from LoginComponent // so that this subcomponent graph needs to satisfy all the dependencies of the // fields that LoginActivity is injecting void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); }

You also must define a subcomponent factory inside LoginComponent so that

ApplicationComponent knows how to create instances of LoginComponent.

Kotlin

@Subcomponent interface LoginComponent { // Factory that is used to create instances of this subcomponent @Subcomponent.Factory interface Factory { fun create(): LoginComponent } fun inject(loginActivity: LoginActivity) }

Java

@Subcomponent public interface LoginComponent { // Factory that is used to create instances of this subcomponent @Subcomponent.Factory interface Factory { LoginComponent create(); } void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); }

To tell Dagger that LoginComponent is a subcomponent of

ApplicationComponent, you have to indicate it by:

Creating a new Dagger module (e.g.

SubcomponentsModule) passing the subcomponent's class to thesubcomponentsattribute of the annotation.Kotlin

// The "subcomponents" attribute in the @Module annotation tells Dagger what // Subcomponents are children of the Component this module is included in. @Module(subcomponents = LoginComponent::class) class SubcomponentsModule {}

Java

// The "subcomponents" attribute in the @Module annotation tells Dagger what // Subcomponents are children of the Component this module is included in. @Module(subcomponents = LoginComponent.class) public class SubcomponentsModule { }

Adding the new module (i.e.

SubcomponentsModule) toApplicationComponent:Kotlin

// Including SubcomponentsModule, tell ApplicationComponent that // LoginComponent is its subcomponent. @Singleton @Component(modules = [NetworkModule::class, SubcomponentsModule::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { }

Java

// Including SubcomponentsModule, tell ApplicationComponent that // LoginComponent is its subcomponent. @Singleton @Component(modules = {NetworkModule.class, SubcomponentsModule.class}) public interface ApplicationComponent { }

Note that

ApplicationComponentdoesn't need to injectLoginActivityanymore because that responsibility now belongs toLoginComponent, so you can remove theinject()method fromApplicationComponent.Consumers of

ApplicationComponentneed to know how to create instances ofLoginComponent. The parent component must add a method in its interface to let consumers create instances of the subcomponent out of an instance of the parent component:Expose the factory that creates instances of

LoginComponentin the interface:Kotlin

@Singleton @Component(modules = [NetworkModule::class, SubcomponentsModule::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { // This function exposes the LoginComponent Factory out of the graph so consumers // can use it to obtain new instances of LoginComponent fun loginComponent(): LoginComponent.Factory }

Java

@Singleton @Component(modules = { NetworkModule.class, SubcomponentsModule.class} ) public interface ApplicationComponent { // This function exposes the LoginComponent Factory out of the graph so consumers // can use it to obtain new instances of LoginComponent LoginComponent.Factory loginComponent(); }

Assigning scopes to subcomponents

If you build the project, you can create instances of both ApplicationComponent

and LoginComponent. ApplicationComponent is attached to the lifecycle of the

application because you want to use the same instance of the graph as long as

the application is in memory.

What's the lifecycle of LoginComponent? One of the reasons why you needed

LoginComponent is because you needed to share the same instance of the

LoginViewModel between Login-related fragments. But also, you want different

instances of LoginViewModel whenever there's a new login flow. LoginActivity

is the right lifetime for LoginComponent: for every new activity, you need

a new instance of LoginComponent and fragments that can use that instance of

LoginComponent.

Because LoginComponent is attached to the LoginActivity lifecycle, you have to

keep a reference to the component in the activity in the same way you kept the

reference to the applicationComponent in the Application class. That way,

fragments can access it.

Kotlin

class LoginActivity: Activity() { // Reference to the Login graph lateinit var loginComponent: LoginComponent ... }

Java

public class LoginActivity extends Activity { // Reference to the Login graph LoginComponent loginComponent; ... }

Notice that the variable loginComponent is not annotated with @Inject

because you're not expecting that variable to be provided by Dagger.

You can use the ApplicationComponent to get a reference to LoginComponent

and then inject LoginActivity as follows:

Kotlin

class LoginActivity: Activity() { // Reference to the Login graph lateinit var loginComponent: LoginComponent // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { // Creation of the login graph using the application graph loginComponent = (applicationContext as MyDaggerApplication) .appComponent.loginComponent().create() // Make Dagger instantiate @Inject fields in LoginActivity loginComponent.inject(this) // Now loginViewModel is available super.onCreate(savedInstanceState) } }

Java

public class LoginActivity extends Activity { // Reference to the Login graph LoginComponent loginComponent; // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject LoginViewModel loginViewModel; @Override protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { // Creation of the login graph using the application graph loginComponent = ((MyApplication) getApplicationContext()) .appComponent.loginComponent().create(); // Make Dagger instantiate @Inject fields in LoginActivity loginComponent.inject(this); // Now loginViewModel is available super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); } }

LoginComponent is created in the activity's onCreate() method, and it'll get

implicitly destroyed when the activity gets destroyed.

The LoginComponent must always provide the same instance of LoginViewModel

each time it's requested. You can ensure this by creating a custom annotation

scope and annotating both LoginComponent and LoginViewModel with it. Note

that you cannot use the @Singleton annotation because it's already been used

by the parent component and that'd make the object an application singleton

(unique instance for the whole app). You need to create a different annotation

scope.

In this case, you could have called this scope @LoginScope but it's not a good

practice. The scope annotation's name should not be explicit to the purpose it

fulfills. Instead, it should be named depending on its lifetime because

annotations can be reused by sibling components such as RegistrationComponent

and SettingsComponent. That's why you should call it @ActivityScope instead

of @LoginScope.

Kotlin

// Definition of a custom scope called ActivityScope @Scope @Retention(value = AnnotationRetention.RUNTIME) annotation class ActivityScope // Classes annotated with @ActivityScope are scoped to the graph and the same // instance of that type is provided every time the type is requested. @ActivityScope @Subcomponent interface LoginComponent { ... } // A unique instance of LoginViewModel is provided in Components // annotated with @ActivityScope @ActivityScope class LoginViewModel @Inject constructor( private val userRepository: UserRepository ) { ... }

Java

// Definition of a custom scope called ActivityScope @Scope @Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME) public @interface ActivityScope {} // Classes annotated with @ActivityScope are scoped to the graph and the same // instance of that type is provided every time the type is requested. @ActivityScope @Subcomponent public interface LoginComponent { ... } // A unique instance of LoginViewModel is provided in Components // annotated with @ActivityScope @ActivityScope public class LoginViewModel { private final UserRepository userRepository; @Inject public LoginViewModel(UserRepository userRepository) { this.userRepository = userRepository; } }

Now, if you had two fragments that need LoginViewModel, both of them are

provided with the same instance. For example, if you have a

LoginUsernameFragment and a LoginPasswordFragment they need to get injected

by the LoginComponent:

Kotlin

@ActivityScope @Subcomponent interface LoginComponent { @Subcomponent.Factory interface Factory { fun create(): LoginComponent } // All LoginActivity, LoginUsernameFragment and LoginPasswordFragment // request injection from LoginComponent. The graph needs to satisfy // all the dependencies of the fields those classes are injecting fun inject(loginActivity: LoginActivity) fun inject(usernameFragment: LoginUsernameFragment) fun inject(passwordFragment: LoginPasswordFragment) }

Java

@ActivityScope @Subcomponent public interface LoginComponent { @Subcomponent.Factory interface Factory { LoginComponent create(); } // All LoginActivity, LoginUsernameFragment and LoginPasswordFragment // request injection from LoginComponent. The graph needs to satisfy // all the dependencies of the fields those classes are injecting void inject(LoginActivity loginActivity); void inject(LoginUsernameFragment loginUsernameFragment); void inject(LoginPasswordFragment loginPasswordFragment); }

The components access the instance of the component that lives in the

LoginActivity object. Example code for LoginUserNameFragment appears in the

following code snippet:

Kotlin

class LoginUsernameFragment: Fragment() { // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel override fun onAttach(context: Context) { super.onAttach(context) // Obtaining the login graph from LoginActivity and instantiate // the @Inject fields with objects from the graph (activity as LoginActivity).loginComponent.inject(this) // Now you can access loginViewModel here and onCreateView too // (shared instance with the Activity and the other Fragment) } }

Java

public class LoginUsernameFragment extends Fragment { // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject LoginViewModel loginViewModel; @Override public void onAttach(Context context) { super.onAttach(context); // Obtaining the login graph from LoginActivity and instantiate // the @Inject fields with objects from the graph ((LoginActivity) getActivity()).loginComponent.inject(this); // Now you can access loginViewModel here and onCreateView too // (shared instance with the Activity and the other Fragment) } }

And the same for LoginPasswordFragment:

Kotlin

class LoginPasswordFragment: Fragment() { // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject lateinit var loginViewModel: LoginViewModel override fun onAttach(context: Context) { super.onAttach(context) (activity as LoginActivity).loginComponent.inject(this) // Now you can access loginViewModel here and onCreateView too // (shared instance with the Activity and the other Fragment) } }

Java

public class LoginPasswordFragment extends Fragment { // Fields that need to be injected by the login graph @Inject LoginViewModel loginViewModel; @Override public void onAttach(Context context) { super.onAttach(context); ((LoginActivity) getActivity()).loginComponent.inject(this); // Now you can access loginViewModel here and onCreateView too // (shared instance with the Activity and the other Fragment) } }

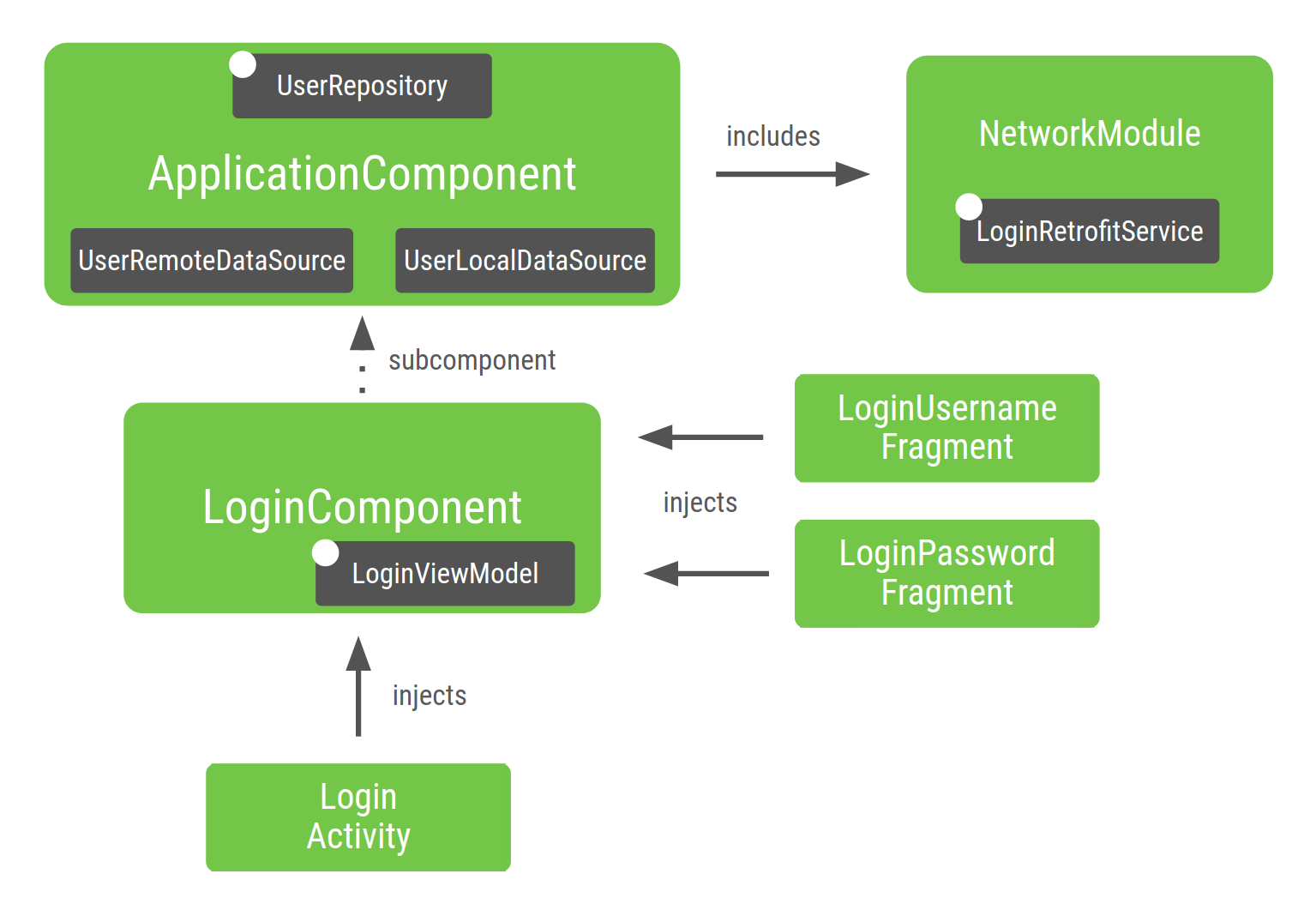

Figure 3 shows how the Dagger graph looks with the new subcomponent. The classes

with a white dot (UserRepository, LoginRetrofitService, and LoginViewModel)

are the ones that have a unique instance scoped to their respective components.

Figure 3. Representation of the graph you built for the Android app example

Let's break down the parts of the graph:

The

NetworkModule(and thereforeLoginRetrofitService) is included inApplicationComponentbecause you specified it in the component.UserRepositoryremains inApplicationComponentbecause it's scoped to theApplicationComponent. If the project grows, you want to share the same instance across different features (e.g. Registration).Because

UserRepositoryis part ofApplicationComponent, its dependencies (i.e.UserLocalDataSourceandUserRemoteDataSource) need to be in this component too in order to be able to provide instances ofUserRepository.LoginViewModelis included inLoginComponentbecause it's only required by the classes injected byLoginComponent.LoginViewModelis not included inApplicationComponentbecause no dependency inApplicationComponentneedsLoginViewModel.Similarly, if you hadn't had scoped

UserRepositorytoApplicationComponent, Dagger would automatically have includedUserRepositoryand its dependencies as part ofLoginComponentbecause that is currently the only placeUserRepositoryis used.

Apart from scoping objects to a different lifecycle, creating subcomponents is a good practice to encapsulate different parts of your application from each other.

Structuring your app to create different Dagger subgraphs depending on the flow of your app helps towards a more performant and scalable application in terms of memory and startup time.

Best practices when building a Dagger graph

When building the Dagger graph for your application:

When you create a component, you should consider what element is responsible for the lifetime of that component. In this case, the

Applicationclass is in charge ofApplicationComponentandLoginActivityis in charge ofLoginComponent.Use scoping only when it makes sense. Overusing scoping can have a negative effect on your app's runtime performance: the object is in memory as long as the component is in memory and getting a scoped object is more expensive. When Dagger provides the object, it uses

DoubleChecklocking instead of a factory-type provider.

Testing a project that uses Dagger

One of the benefits of using dependency injection frameworks like Dagger is that it makes testing your code easier.

Unit tests

You don't have to use Dagger for unit tests. When testing a class that uses constructor injection, you don't need to use Dagger to instantiate that class. You can directly call its constructor passing in fake or mock dependencies directly just as you would if they weren't annotated.

For example, when testing LoginViewModel:

Kotlin

@ActivityScope class LoginViewModel @Inject constructor( private val userRepository: UserRepository ) { ... } class LoginViewModelTest { @Test fun `Happy path`() { // You don't need Dagger to create an instance of LoginViewModel // You can pass a fake or mock UserRepository val viewModel = LoginViewModel(fakeUserRepository) assertEquals(...) } }

Java

@ActivityScope public class LoginViewModel { private final UserRepository userRepository; @Inject public LoginViewModel(UserRepository userRepository) { this.userRepository = userRepository; } } public class LoginViewModelTest { @Test public void happyPath() { // You don't need Dagger to create an instance of LoginViewModel // You can pass a fake or mock UserRepository LoginViewModel viewModel = new LoginViewModel(fakeUserRepository); assertEquals(...); } }

End-to-end tests

For integration tests, a good practice is to create a

TestApplicationComponent meant for testing.

Production and testing use a different component configuration.

This requires more up-front design of the modules in your application. The testing component extends the production component and installs a different set of modules.

Kotlin

// TestApplicationComponent extends from ApplicationComponent to have them both // with the same interface methods. You need to include the modules of the // component here as well, and you can replace the ones you want to override. // This sample uses FakeNetworkModule instead of NetworkModule @Singleton @Component(modules = [FakeNetworkModule::class, SubcomponentsModule::class]) interface TestApplicationComponent : ApplicationComponent { }

Java

// TestApplicationComponent extends from ApplicationComponent to have them both // with the same interface methods. You need to include the modules of the // Component here as well, and you can replace the ones you want to override. // This sample uses FakeNetworkModule instead of NetworkModule @Singleton @Component(modules = {FakeNetworkModule.class, SubcomponentsModule.class}) public interface TestApplicationComponent extends ApplicationComponent { }

FakeNetworkModule has a fake implementation of the original NetworkModule.

There you can provide fake instances or mocks of whatever you want to replace.

Kotlin

// In the FakeNetworkModule, pass a fake implementation of LoginRetrofitService // that you can use in your tests. @Module class FakeNetworkModule { @Provides fun provideLoginRetrofitService(): LoginRetrofitService { return FakeLoginService() } }

Java

// In the FakeNetworkModule, pass a fake implementation of LoginRetrofitService // that you can use in your tests. @Module public class FakeNetworkModule { @Provides public LoginRetrofitService provideLoginRetrofitService() { return new FakeLoginService(); } }

In your integration or end-to-end tests, you'd use a TestApplication that

creates the TestApplicationComponent instead of an ApplicationComponent.

Kotlin

// Your test application needs an instance of the test graph class MyTestApplication: MyApplication() { override val appComponent = DaggerTestApplicationComponent.create() }

Java

// Your test application needs an instance of the test graph public class MyTestApplication extends MyApplication { ApplicationComponent appComponent = DaggerTestApplicationComponent.create(); }

Then, this test application is used in a custom TestRunner that you'll use to

run instrumentation tests. For more information about this, check out the Using

Dagger in your Android app codelab.

Working with Dagger modules

Dagger modules are a way to encapsulate how to provide objects in a semantic way. You can include modules in components but you can also include modules inside other modules. This is powerful, but can be easily misused.

Once a module has been added to either a component or another module, it's already in the Dagger graph; Dagger can provide those objects in that component. Before adding a module, check if that module is part of the Dagger graph already by checking if it's already added to the component or by compiling the project and seeing if Dagger can find the required dependencies for that module.

Good practice dictates that modules should only be declared once in a component (outside of specific advanced Dagger use cases).

Let's say you have your graph configured in this way. ApplicationComponent

includes Module1 and Module2 and Module1 includes ModuleX.

Kotlin

@Component(modules = [Module1::class, Module2::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module(includes = [ModuleX::class]) class Module1 { ... } @Module class Module2 { ... }

Java

@Component(modules = {Module1.class, Module2.class}) public interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module(includes = {ModuleX.class}) public class Module1 { ... } @Module public class Module2 { ... }

If now Module2 depends on classes provided by ModuleX. A bad practice

is including ModuleX in Module2 because ModuleX is included twice in

the graph as seen in the following code snippet:

Kotlin

// Bad practice: ModuleX is declared multiple times in this Dagger graph @Component(modules = [Module1::class, Module2::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module(includes = [ModuleX::class]) class Module1 { ... } @Module(includes = [ModuleX::class]) class Module2 { ... }

Java

// Bad practice: ModuleX is declared multiple times in this Dagger graph. @Component(modules = {Module1.class, Module2.class}) public interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module(includes = ModuleX.class) public class Module1 { ... } @Module(includes = ModuleX.class) public class Module2 { ... }

Instead, you should do one of the following:

- Refactor the modules and extract the common module out to the component.

- Create a new module with the objects that both modules share and extract it out to the component.

Not refactoring in this way results in a lot of modules including each other without a clear sense of organization and making it more difficult to see where each dependency is coming from.

Good practice (Option 1): ModuleX is declared once in the Dagger graph.

Kotlin

@Component(modules = [Module1::class, Module2::class, ModuleX::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module class Module1 { ... } @Module class Module2 { ... }

Java

@Component(modules = {Module1.class, Module2.class, ModuleX.class}) public interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module public class Module1 { ... } @Module public class Module2 { ... }

Good practice (Option 2): Common dependencies from Module1 and Module2

in ModuleX are extracted out to a new module named ModuleXCommon that is

included in the component. Then two other modules named

ModuleXWithModule1Dependencies and ModuleXWithModule2Dependencies are

created with the dependencies that are specific to each module. All modules

are declared once in the Dagger graph.

Kotlin

@Component(modules = [Module1::class, Module2::class, ModuleXCommon::class]) interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module class ModuleXCommon { ... } @Module class ModuleXWithModule1SpecificDependencies { ... } @Module class ModuleXWithModule2SpecificDependencies { ... } @Module(includes = [ModuleXWithModule1SpecificDependencies::class]) class Module1 { ... } @Module(includes = [ModuleXWithModule2SpecificDependencies::class]) class Module2 { ... }

Java

@Component(modules = {Module1.class, Module2.class, ModuleXCommon.class}) public interface ApplicationComponent { ... } @Module public class ModuleXCommon { ... } @Module public class ModuleXWithModule1SpecificDependencies { ... } @Module public class ModuleXWithModule2SpecificDependencies { ... } @Module(includes = ModuleXWithModule1SpecificDependencies.class) public class Module1 { ... } @Module(includes = ModuleXWithModule2SpecificDependencies.class) public class Module2 { ... }

Assisted injection

Assisted injection is a DI pattern that is used to construct an object where some parameters may be provided by the DI framework and others must be passed in at creation time by the user.

In Android, this pattern is common in details screens where the id of the element to show is only known at runtime, not at compile time when Dagger generates the DI graph. To learn more about assisted injection with Dagger, see the Dagger documentation.

Conclusion

If you haven't already, review the best practices section. To see how to use Dagger in an Android app, see the Using Dagger in an Android app codelab.